Read LvBS interview with Tracey Power, Managing Director at Implemental and Implemental liaison lead for the ‘Leaders for Mental Health’ Programme, and Jonathan Rolfe, Director of Business Strategy & Operations at Implemental and Implemental liaison co-lead for the ‘Leaders for Mental Health’ Programme, to find out the difference between British and Ukrainian mental health sectors, challenges mental sector reformers face and the ways how to make fewer mistakes.

Tell us how the processes of deinstitutionalization of the Mental health sector took place in Britain?

The process to close the institutions and develop a network of community services took place over many decades. It was driven by published government strategy and policy and was carried out with the support of national guidance and associated implementation plans. It succeeded because there was a heavy emphasis on involving all stakeholders to play their part in identifying needs, developing new services and facilitating collaborative partnerships at a local level. And ultimately this relied on the enthusiasm and determination of leaders within all parts of the service system.

What phases of transformation could you note in this “painless revolution”?

There were a number of elements of the change process which were implemented in parallel. Hospital closure plans were developed down to the level of individual plans for every service user, many of whom had lived for many years in institutions. These plans included developing a range of residential and rehabilitation services that enabled people with severe and enduring mental health problems to return to their communities of origin and reinstate their relationships with family and friends. Also, plans to integrate psychiatric services into local general hospitals by developing mental health units with specialist beds and outpatient services. The key to the plans was developing community mental health teams to support people out of the hospital. This included working closely with primary care colleagues to provide assessment and brief treatment for those experiencing common mental health problems. Also, care management for people with more complex and enduring needs to maximise independence and minimise the impact of mental health crises by co-ordinating a range of health and social care supports. The common thread for these transformation elements was the empowerment of service users and their families.

Which of them were the most difficult during the reform and why?

The biggest challenge was to change peoples’ minds, not only amongst mental health professionals but also service users, their families and the wider community. Managing change always requires a lot of time and energy. Many people were sceptical about ‘community care’, they were anxious about the right supports being available in the community, staff learning new skills, service user becoming more independent. But early studies demonstrated that the new arrangements did work and then the reform process became a global movement.

How long did it take Britain to achieve the settled results?

It is important to say that Britain is still on a journey to provide the best range of services possible. The hospital closure process was at its height in the 1980s and 1990s. The very influential publication of the National Service Framework in 1999 kick-started ten years of community developments, with associated funding, which included the provision of early intervention, assertive outreach and crisis resolution services (amongst many other areas of delivery). The last decade was characterised by disinvestment, pressure on hospital beds and long waiting lists for specialist psychological interventions. It would be fair to say that the developments took place over a forty or fifty-year period.

The main problems that deinstitutionalization solves in the sector of Mental health care services?

The old institutions provided outdated and often inadequate services and people often spent many years there, a long way from friends and family. The residents had a very poor quality of life and little independence. There was a significant stigma associated with being in psychiatric care and people with mental health problems were discriminated against in their daily lives.

New service systems build support around the needs of individuals and based on living a fulfilling life in the community. Meeting mental health needs is considered the responsibility of a wide range of organisations and there is equal emphasis on mental health promotion and each citizen taking some responsibility for their own wellbeing. It is possible to target public resources at those most in need and to promote maximum independence so people become less reliant on services.

How do you assess the current situation in the Mental health care sector in Ukraine?

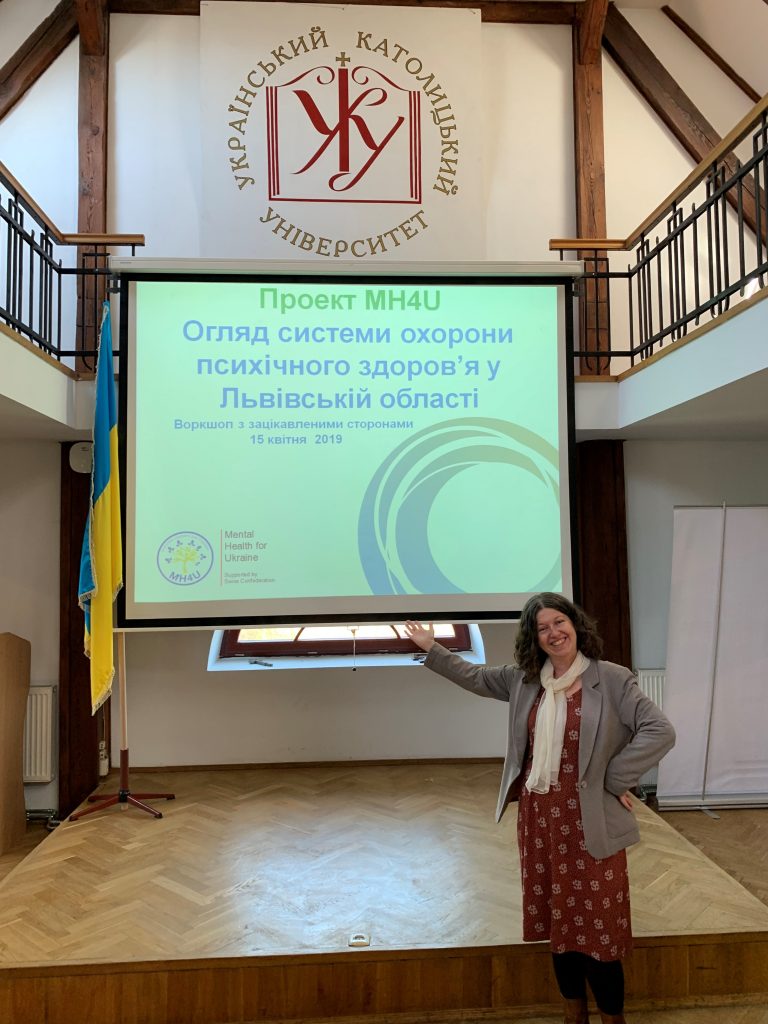

Ukraine is at the beginning of a long journey to develop and transform its services for people with mental health problems but it has the benefit of learning from many other countries and the support of a wide range of agencies e.g., WHO, SDC etc. The MH4U project has a number of workstreams designed to support the Ministries, the NHS and a wide range of health, social care and NGO providers and other stakeholders. The Consortium includes Implemental, a not for profit organisation working with colleagues all over the world to improve mental health and wellbeing. Implemental brings experience and expertise in a range of mental health development programmes and is playing a key role in the ‘Leaders for Mental Health’ development programme.

Why did you choose LvBS for partnership in this project?

LvBS has very relevant experience in providing capacity-building support to health professionals. LvBS colleagues are very collaborative and see the merits of bringing together a wide range of perspectives to the ‘Leaders for Health’ programme.

What are the goals you want to achieve with this project in Ukraine and which indicators would you apply to define the success of it?

The overarching aim is to support and enable leaders to play a key role in developments in their local areas. In particular, to facilitate the operation of Local Implementation Teams (LITs) to develop, implement and evaluate local plans. The ‘Leaders for Health’ programme will be successful if participants have made strong relationships with a wide range of stakeholders in their local area, have been able to identify local needs and priorities for action, and have been able to develop, implement and evaluate a specific project integral to an overall LIT action plan.