Gerrit Anton de Waal, Amy L. Kenworthy, Sophia Opatska, Olena Trevoho, Yaryna Boychuk, Valeria Kozlova

ABSTRACT

This study investigates the dynamic pathways of organisational resilience among Ukrainian firms operating in a war economy. Our research highlights the profound impact of armed conflicts on commerce, emphasising the need for businesses to develop resilience strategies to mitigate risks and maintain operations. Through an examination of organisational data representing the 2-year period following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, our findings support the presence of two resilience pathways previously described in the extant literature, ‘bounce-back’ and ‘bounce-beyond’ and expose two new pathways which we have labelled ‘bounce-less’ and ‘bounce-boom.’ Our findings reveal the complex and varying paths of organisational resilience resulting from changes in market demand and resource availability, underscoring the importance of organisational adaptability, resourcefulness and innovation. We also propose a broader definition of resilience than is currently found in the literature – one which recognises the challenges of achieving a baseline of organisational survival in a time of crisis. The article concludes with practical implications and recommendations for future research on resilience in wartime conditions.

1 Introduction

Organisational resilience is an extensively discussed theoretical concept representing the capacity of businesses to adapt, recover, and thrive amidst disruptions (Garrido-Moreno et al. 2024; Maor et al. 2024). Existing literature has explored resilience in various adverse contexts including violent protests (Dimitriadis 2021), natural disasters (Monllor and Murphy 2017), global economic crises (Ling et al. 2023), disruptive business models (Dewald and Bowen 2010), and wars (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011).

Our research extends the current literature by empirically and longitudinally exploring the phenomenon of organisational resilience within the context of war. As research team, we were driven to explore this topic area because of the first-hand experience of four of our members who are academics teaching within the MBA programme of a well-known Ukrainian university. Each of these co-authors has been living and working in situ in XX (city deleted for anonymity), Ukraine throughout most, if not all, of the war. As a team of six academics, we stand firmly together in the belief there are many untold stories and valuable lessons of resilience to be learned from the experiences of Ukrainians as they endure this ongoing crisis (United Nations 2025). As people who are having parts of their culture erased through the intentional targeting and destruction of cultural artifacts and historical monuments (Farago et al. 2024), the recording of personal, institutional, and cultural knowledge through case writing, interviews, media outreach, and other forms of sharing their stories has become critical to their survival. Resilience, itself, has become critical to their survival (Opatska et al. 2023). As such, we view this study as a response to ‘an urgent call to collaborate with colleagues in crisis environments around the world’ (Kenworthy et al. 2025) through which we can capture Ukrainian organisational paths to resilience today, so others can learn from them tomorrow.

Research is only beginning to explore the disruptions and complexities stemming from war and their resultant and significant impacts on industry and global commerce; this is a critical area for current research given the fact that we are living in a time of steadily increasing geopolitical unrest (Stares 2025). War and armed conflict are contemporary issues affecting billions of people globally, and insights gained can help alleviate challenges for organisations caught in, drawn into, or otherwise affected by this type of crisis. From an academic perspective, Su and Junge (2023) note gaps in understanding how war affects resilience processes and outcomes, suggesting the need for more comprehensive research in this area. Extending this study, and specific to the war environment we examine here, Clark (2024) emphasises the need for nuanced, multi-systemic approaches to fully understand resilience in the context of what is currently happening in Ukraine. Although several studies highlight the importance of measuring organisational resilience (Ilseven and Puranam 2021; Kantur 2015; Williams et al. 2017), to date we know of no other empirical research using longitudinal data within an environment of war to examine pathways of organisational resilience.

The research question that lies at the heart of this study is: what are the various resilience response pathways exhibited by Ukrainian firms operating within war? We were interested in exploring not only the organisational resilience pathways, but also their organisational implications. To do this, we collected organisational-level data representing three time points falling between January 2022 and May 2024. We acknowledge that as the war continues, these insights represent a dynamic situation with uncertain outcomes.

The findings from our research provide three notable contributions for understanding organisational resilience within the crisis context of war: (1) we empirically validate the two organisational resilience response paths currently described in the extant literature which are ‘bounce-back’ and ‘bounce-beyond’ (Hoegl and Hartmann 2020; Smith et al. 2008), (2) we identify and contribute two new response paths to the literature which we have labelled ‘bounce-less’ and ‘bounce-boom’ and (3) we re-define and extend the ‘bounce-back’ pathway to include firms which have not yet returned to precrisis revenue levels, but are moving in that direction. Here, we are removing the criterion that ‘bounce-back’ resilience pathways should only include firms which have returned to precrisis revenue levels. We argue that those organisations on a revenue-increasing pathway/trajectory in which they are moving towards where they were pre-shock should be categorised as ‘bouncing back.’ We believe this is particularly important to recognise for organisations operating within an environment of war.

With respect to our new path of ‘bounce-less’ and our redefinition of ‘bounce-back’, our contribution is the expansion of what it means to demonstrate organisational resilience in the context of war as a crisis. With significant shocks like the one faced by all Ukrainian firms following Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, to still have an operational organisation is clearly a demonstration of resilience. We explore these contributions within the paper as follows. First, we contextualise and share our definition of organisational resilience. Then we provide an overview of what is known about organisational resilience in the context of war. Next, we transition into our methodology, results, and analysis. Finally, we provide practical implications and concluding remarks with reflections on limitations and future research directions.

2 Understanding Organisational Resilience

Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) define organisational resilience as the ability to absorb, adapt, and transform in response to unexpected circumstances. According to this view, resilience is not only bouncing back from adversity but also learning from the experience, reactively, to improve future performance. Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) extend this definition by describing organisational resilience as the capacity to develop and leverage organisational resources, both internal and external, to cope with, adapt to, and grow from significant disruptions and changes. This perspective suggests resilience is not something derived exclusively from internal resources, rather, it is heavily dependent upon external resources as well.

Other definitions of organisational resilience emphasise the ability of an organisation to bounce back from setbacks (Hamel and Välikangas 2003; Manfield and Newey 2018), including a focus on the significance of innovation and flexibility (Fiksel et al. 2014). In addition to viewing resilience as performance recovery (i.e., bounce back), researchers have included a categorisation known as bounce beyond (or bounce forward) describing organisational outcomes which exceed performance before the crisis (Bartuseviciene et al. 2022; Mihotić et al. 2023). Across all of these definitions, we see the underlying message that to remain resilient in the face of disruptions, such as temporary or permanent changes in market demand, organisations must constantly explore novel approaches to conducting business.

Drawing upon the above, we define organisational resilience as an organisation’s proactive and reactive ability to dynamically adapt and evolve as its market is evolving, to respond to exogeneous shocks, and to shape itself in response to long term challenges. In doing so, we acknowledge that organisational resilience is a complex and multifaceted concept, and its understanding may vary across disciplines and contexts. In management research, the proactive approach relates to risk management, while the reactive approach is a post-event organisational response (Fiksel et al. 2014). Other insightful differences between the two perspectives of resilience include a focus on an organisation’s general potential or capacity (proactive perspective) (Moenkemeyer et al. 2012; Stoverink et al. 2020) versus its outcomes achieved (reactive perspective) (Britt et al. 2016; DesJardine et al. 2019). As our research purposefully considers ‘resilience-in-action’ following a crisis shock, we are only able to investigate organisations’ reactive abilities, which we both conceptualise and operationalise as their resilience paths.

3 Organisational Resilience in the Context of War

To comprehend the urgency of studying the resilience of organisations in wartime, it is crucial to appreciate the current state of global conflicts and their devastating impact on commerce. According to the Geneva Academy (2025), there are more than 110 armed conflicts taking place throughout the world. These conflicts range from large-scale wars to localised insurgencies, and their effects are felt not only in the countries directly involved but also across the global economy. Current ‘rising conflict and geopolitical divisions’ have led to ‘no fewer than 181 million people in 72 countries’ who need humanitarian aid and protection (UNDP 2024). The data are clear – we are a world in crisis and Ukraine is a country at war.

Although the terms war and crisis are not synonymous, we refer to Brecher (1996) seminal description of how they are linked. In short, a crisis can erupt, persist, and terminate with or without violence. War does not eliminate or replace crisis. Rather, crisis is accentuated by war (p 128). To explore the impact of war, which in this context also refers to armed conflict (e.g., [Idler 2024]), on the need for organisational resilience requires an understanding of a variety of factors.

First, these types of crises disrupt supply chains, leading to shortages of essential goods and services, including raw materials needed for production. This disruption can have severe consequences for companies that rely on global sourcing and distribution networks. In the case of Ukraine, which Nataliya Katser-Buchkovska, founder of the Green Resilience Facility, referred to as ‘a vital part of the global supply chain for critical materials’ in a 2024 World Economic Forum article, the war has dramatically impacted global access to goods in sectors including energy, agriculture, military-industrial capabilities, and raw materials (Katser-Buchkovska 2024; Ollagnier 2022).

Second, war often results in the destruction of physical infrastructure, including factories, warehouses, and transportation networks. Ukraine, for example, has suffered extensive infrastructure losses (Carr and Zachmann 2024; Statista 2023). Such destruction not only hinders economic development but also poses significant challenges for businesses operating in war-torn regions.

Additionally, war creates an atmosphere of uncertainty and instability, which can deter foreign direct investment (FDI) and hinder economic growth. The Institute of Economics and Peace’s Global Peace Index (GPI) highlights the negative correlation between peace and economic freedom (Jelloian 2023). Countries with higher levels of peace and stability tend to attract more investment and experience higher economic growth rates. Conversely, countries embroiled in conflicts face reduced investment, decreased productivity, and increased business risks (Abdalhalim and Halkias 2015; Iqbal et al. 2019).

In terms of organisational resilience in response to adverse environmental conditions, it is often conceptualised along the three phases of precrisis (anticipation), during-crisis (coping), and post-crisis (recovery and learning) (Tekletsion et al. 2024). However, as recent research has identified, with respect to the war in Ukraine, the last two phases are overlapping because elements of engaging in learning, focusing on future-preparedness, and anticipating what will be needed post-crisis (i.e., for recovery) are all elements which were required for organisational leaders during the crisis itself (Opatska et al. 2023). The authors highlight the unique challenges and characteristics of crisis management in wartime situations, likening it to a ‘cosmology episode’ where the usual sense of order collapses, making it difficult to prepare for and effectively navigate within. The managers interviewed in their study emphasised the importance of safety and caring for their employees and their families. They also mentioned the need for quick decision-making and frequent communication during the crisis. The study found that war as a crisis type is different from other types of crises due to factors such as the lack of a known endpoint, the loss of personnel, and the close connection between company purpose and the war effort of the country. The study also identified the importance of anticipation, resilience, crisis leadership, and internal crisis communication in wartime crisis management.

In addition to the points discussed above, organisations operating under wartime conditions must consider a broad range of resilience dimensions. These include flexibility, resourcefulness, and learning capacity (Kantur 2015), as well as the adaptability and robustness of their systems and processes (Ilseven and Puranam 2021). A critical aspect of resilience is the ability to learn from past crises, recognising that each crisis presents a unique learning opportunity. This perspective is especially important in the context of war, where the duration and consequences are often unpredictable, necessitating long-term organisational planning (Obłój and Voronovska 2024).

While these various elements are essential, organisations must not overlook the profound impact that war can have on their resource base. Access to, and the management of, key resources become central concerns in both the immediate response and long-term recovery. Therefore, when studying organisational resilience and exploring recovery pathways, it is crucial to focus on how firms secure and utilise their resources during crisis situations.

Our research addresses this specific aspect by examining the role of organisational resources in resilience, using data collected during an ongoing war. By assessing the effects of war on firms’ resources and turnover, we provide valuable insights into how organisations navigate and adapt to significant disruptions in both their external environment-such as fluctuating demand-and their internal environment-such as resource shocks affecting staff, assets, raw materials, capital, and equipment.

Liu et al. (2021) identified several factors influencing organisational resilience, including resources, capabilities, relationships, communication, social capital, strategy, learning, and work passion. However, their findings highlighted organisational resources as the most critical factor. Guided by this evidence, our study focuses on organisational resources and to ensure the manageability of our survey while capturing the most impactful dimensions. Specifically, we draw on Liu et al.’s (2021) sub-categories – human resources (staff), finances (capital), and materials – along with business infrastructure (buildings) and tangible assets (such as machinery and equipment), which are commonly recognised as types of physical resources (Barney 1991). This approach aligns with the resource-based view of the organisation and allows us to deepen our understanding of the pivotal role resources play in organisational resilience during crisis conditions.

In a war that has resulted in approximately 64% of micro, small, and medium enterprises either suspending operations or closing their businesses (UNDP 2024), each organisation we are studying here has something to teach us in terms of resilience.

4 Methodology

We employed a quantitative research methodology by administering an online survey which included 26 questions (9 demographic and 17 content-related) and was sent, unsolicited and written in Ukrainian, to an initial sample of 24 organisational leaders from various Ukrainian firms. The survey items in both Ukrainian and English, along with a document detailing the justification for the use of the scales and relevant references, have been provided as supplementary materials and are available in a Figshare repository (de Waal et al. 2025). The remaining respondents were acquired through snowball sampling. The requirements for participation were that we have only one organisational leader per firm and that the respondent must be an executive level decision maker within a Ukrainian organisation. Our research team includes two researchers from XX University in Australia and four researchers from XX University in Ukraine. Three members of the Ukrainian team are bilingual and ensured accurate translation of the survey questions from English to Ukrainian to minimise translation bias. Research ethics approvals were acquired from both institutions with voluntary participation requested through one email invitation.

In total, we received 349 responses between February 2024 and May 2024, with a significant portion (256 = 73%) that had missing data making them unusable. After cleaning the data, we were left with 75 complete respondent data-sets. We believe the high number of incomplete responses was due to the complexity and length of the survey as well as the challenging circumstances faced by the respondents, who were likely preoccupied with personal and organisational issues related to the war, making survey completion a low priority. Despite this, with an unsolicited and voluntary request for participation, we consider a 27% fully usable response rate which represents data from 75 unique Ukrainian organisations over a 2+ year period within war to be remarkable. Given the crisis environment our respondents were (and still are) living within, we are immensely grateful for the time and information each respondent contributed to our research.

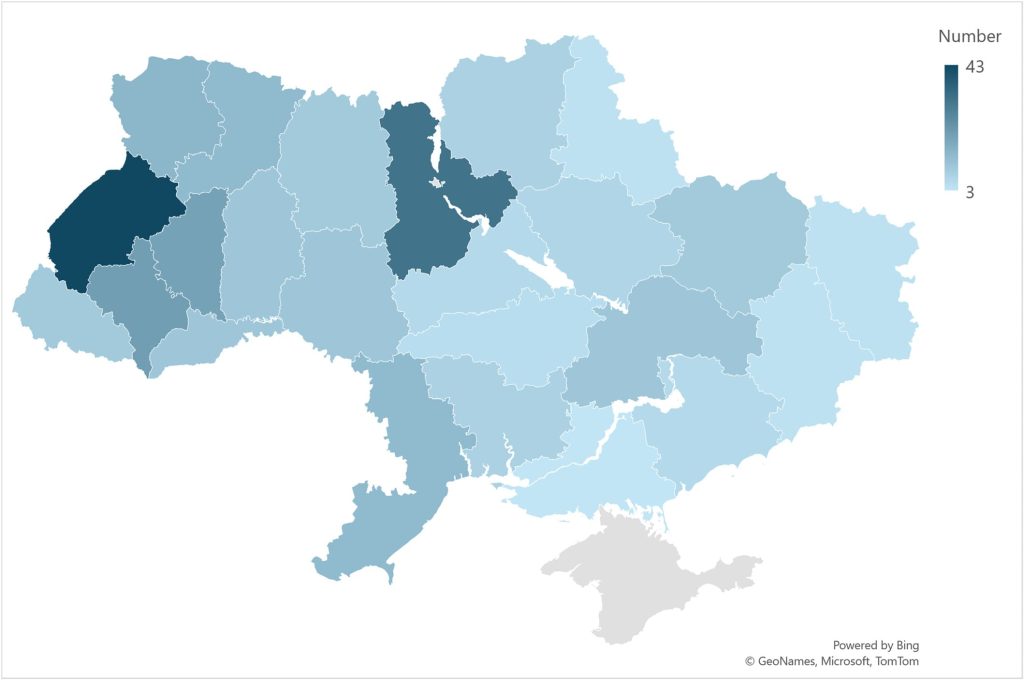

Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of firms represented by our respondents across various regions (oblasts) in Ukraine.

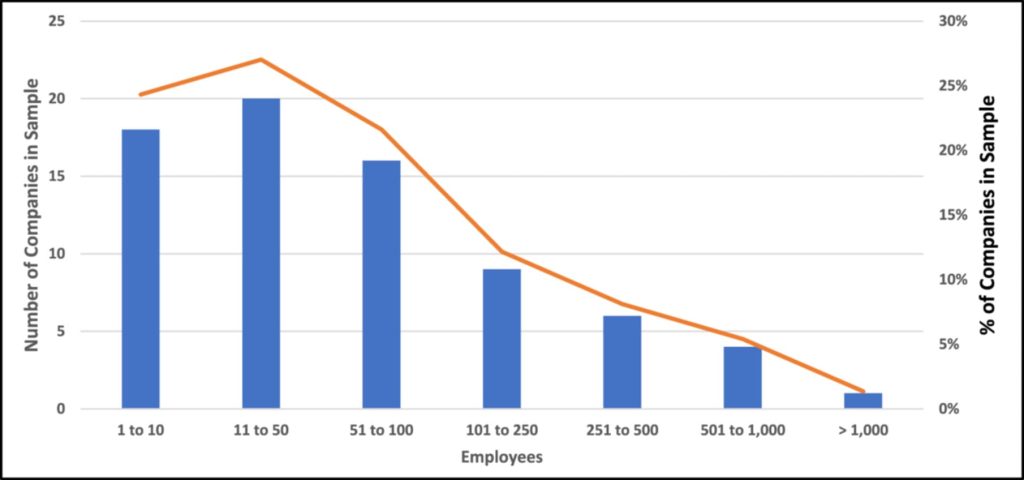

Approximately 85% of our sample’s participants run businesses with fewer than 250 full-time equivalent employees, as shown in Figure 2, and can therefore be considered as small-to-medium size enterprises (SMEs). Compared to larger organisations, SMEs face specific challenges such as limited financial and human resources, making them potentially more vulnerable to disruptions caused by adverse events (De Matteis et al. 2023).

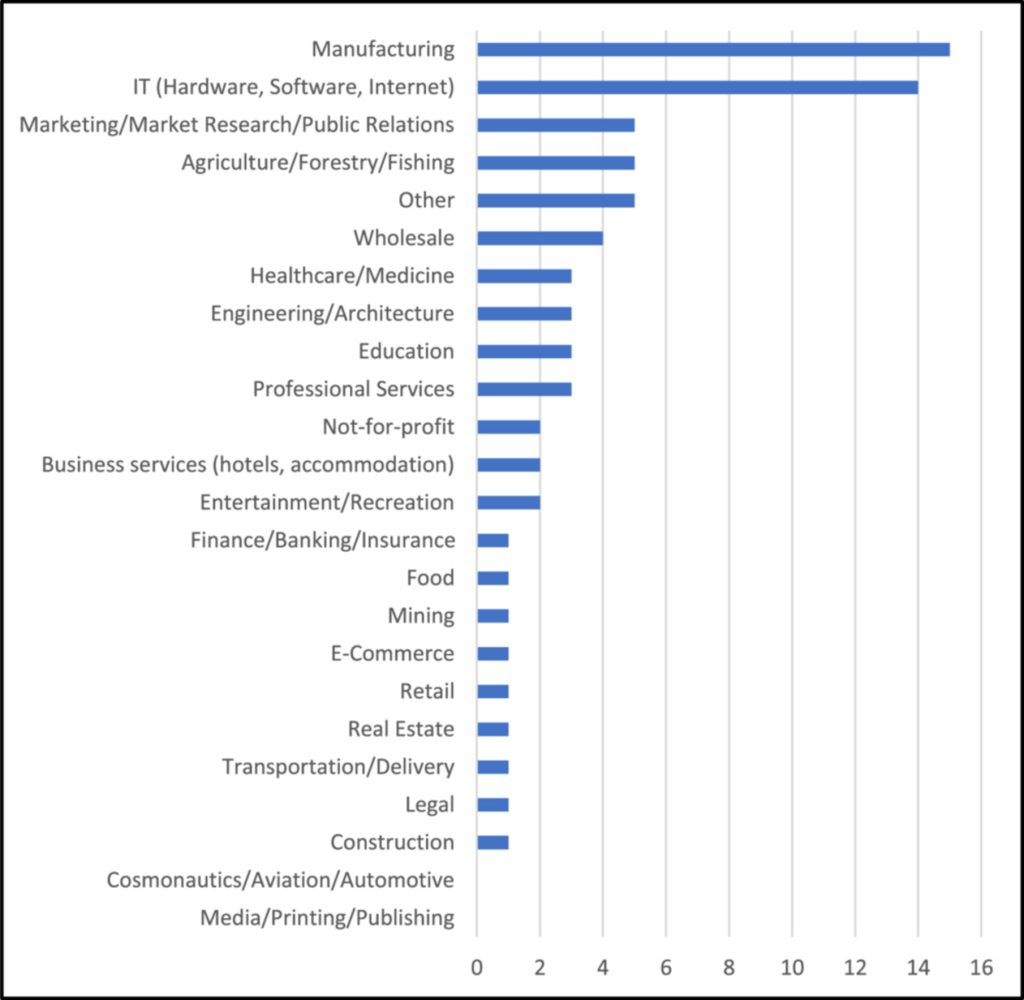

Figure 3 provides a breakdown of the participating firms by industry.

We retrospectively collected longitudinal data on firm revenue and resource availability over three consecutive time intervals following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine which took place on February 24, 2022. Organisational data were provided for each of the following dates: January 2022 (as the 0% change pre-war reference point), March 2022 (i.e., immediately following the crisis shock of the full-scale invasion), March 2023 (i.e., 1 year of operating within war), and March 2024 (i.e., 2 years of operating within war). This approach allowed us to visually observe patterns and trends over a 2-year period and make inferences regarding how the war impacted firms and how their resilient behaviour influenced overall firm performance. Given our research interest and small sample size, we analysed the data using simple descriptive statistics and visual presentations.

5 Results and Analysis

5.1 Revenue Response Paths Analysis

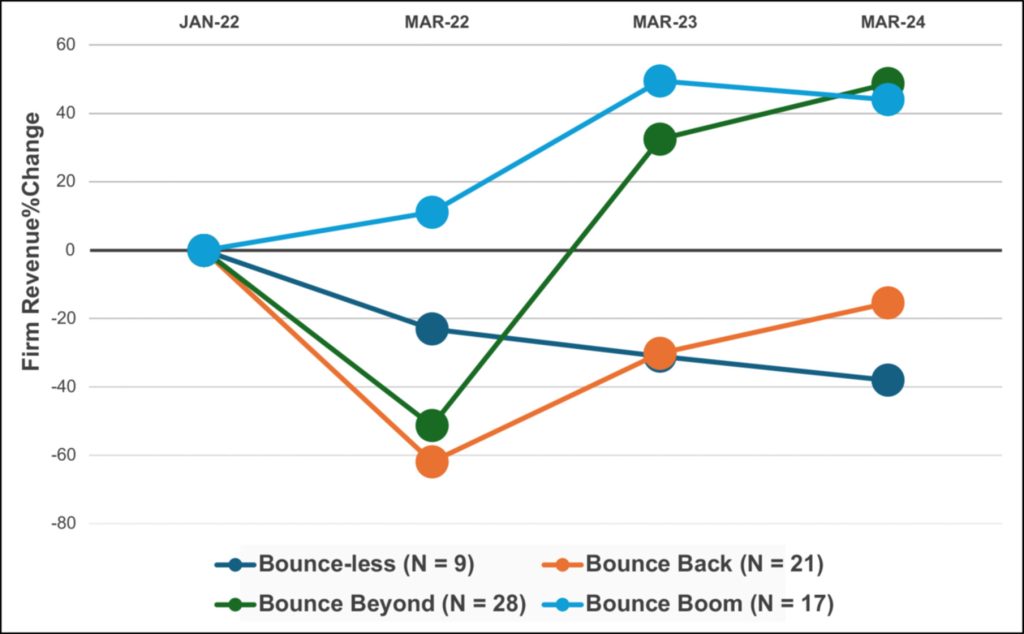

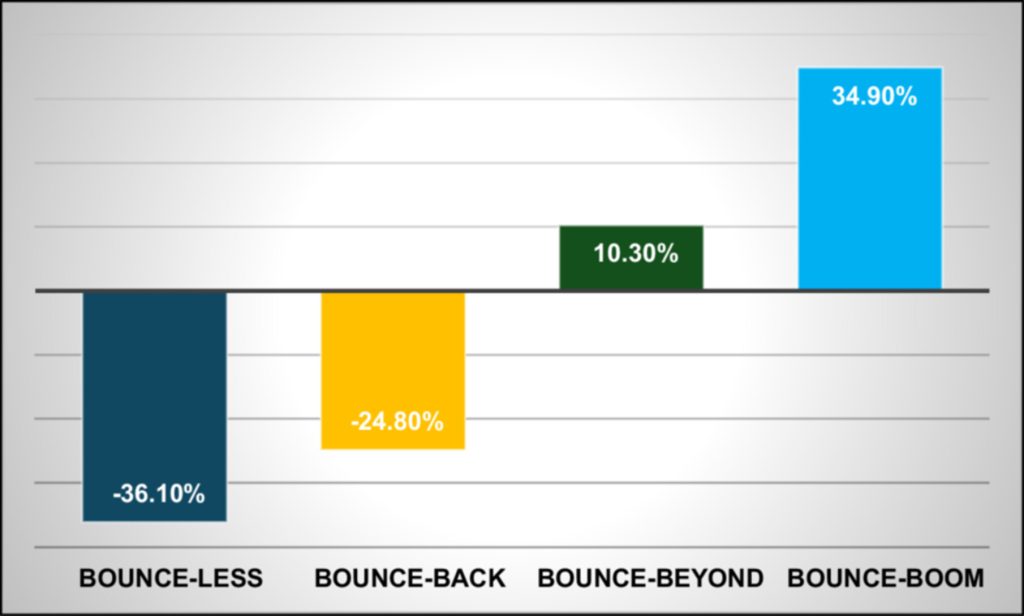

The primary objective of our study was to assess the impact of the war on the revenue of the firms in our sample. A visual inspection of the averaged revenue profiles revealed four revenue response paths of firms that represent the emergent outcomes of heterogeneous firm-level interactions with external shocks and internal capabilities, as shown in Figure 4. We recognise that the key factors influencing resilience, such as demand fluctuations and resource availability, may differ among these groups. However, this does not impact our analysis as it is centred on categorising the net effects of these interactions into distinct revenue pathways. Two of the response paths have been discussed in the extant literature (bounce-back and bounce-beyond) and two are new paths identified within our research here (bounce-less and bounce-boom). We refer to these trajectories as organisational resilience pathways from this point forward.

The relationship between revenue and market demand requires some clarification. While revenue is often influenced by demand, they are distinct constructs, particularly in crisis contexts. Revenue reflects actualised sales, shaped not only by demand but also by a firm’s capacity to convert demand into transactions. Market demand, by contrast, represents the potential sales a firm could achieve under ideal conditions. Crucially, supply-side constraints, such as disruptions to human capital, infrastructure, or raw materials, can decouple revenue from demand. For example:

- Increased demand may not translate to higher revenue if a firm lacks the resources (e.g., staff, equipment) to scale production or delivery.

- Decreased demand might not proportionally reduce revenue if a firm pivots to alternative markets or adjusts pricing strategies.

In wartime, such disconnects are amplified. Firms may face surges in demand for critical goods (e.g., medical supplies) but struggle to meet it due to bombed infrastructure or staff shortages. Conversely, demand for non-essential goods may collapse, but resilient firms could offset losses by reallocating resources to new opportunities.

Hence, our study intentionally treats revenue and market demand as independent variables to isolate the role of resource shocks in mediating this relationship. This approach aligns with crisis management literature, which emphasises that supply-side disruptions (e.g., resource depletion) often overshadow demand-side fluctuations in determining firm outcomes (Sheffi 2005; Williams et al. 2017). By controlling for demand changes, we focus on how firms’ resource resilience, their ability to protect, adapt or reallocate resources, shapes their capacity to capitalise on (or mitigate) shifts in demand.

We acknowledge this as a simplifying assumption but argue it is both methodologically necessary and theoretically justified in contexts where supply-chain and resource disruptions dominate economic dynamics.

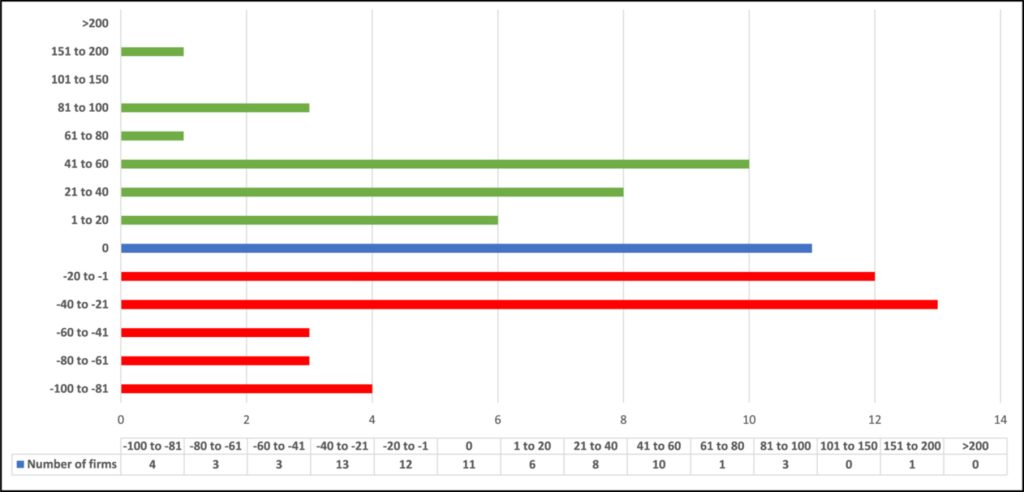

5.2 Change in Market Demand

Since the commencement of the war in February 2022, a considerable portion of firms represented in the study have observed substantial declines in demand for their primary product or service offerings (Figure 5). In total, 46.7% of the participating firms experienced a downturn in demand. A significant portion of this group, representing 30.7% of the total number of firms, reported declines in demand of greater than 20%. Conversely, 38.7% of the firms observed significant increases in demand for their offerings. This increase is divided into two groups: 5.3% of the firms experienced growth between 81% and 200 + %, while the remaining 33.3% reported growth in the range of 1% to 80%. Interestingly, 14.7% of the firms reported that the war conditions had no impact on the level of demand for their products or services.

Next, we evaluated the average change in market demand (MD) for each firm’s products and/or services across the four revenue paths, as depicted in Figure 6, 2 months after the initial shock. Firms in the two leftmost categories reported average demand drops of −36% and −25%, respectively, while firms in the two rightmost categories saw sudden demand increases of approximately 10% and 35%. These demand distributions align with the observed revenue pathways.

5.3 Change in Firm Resources

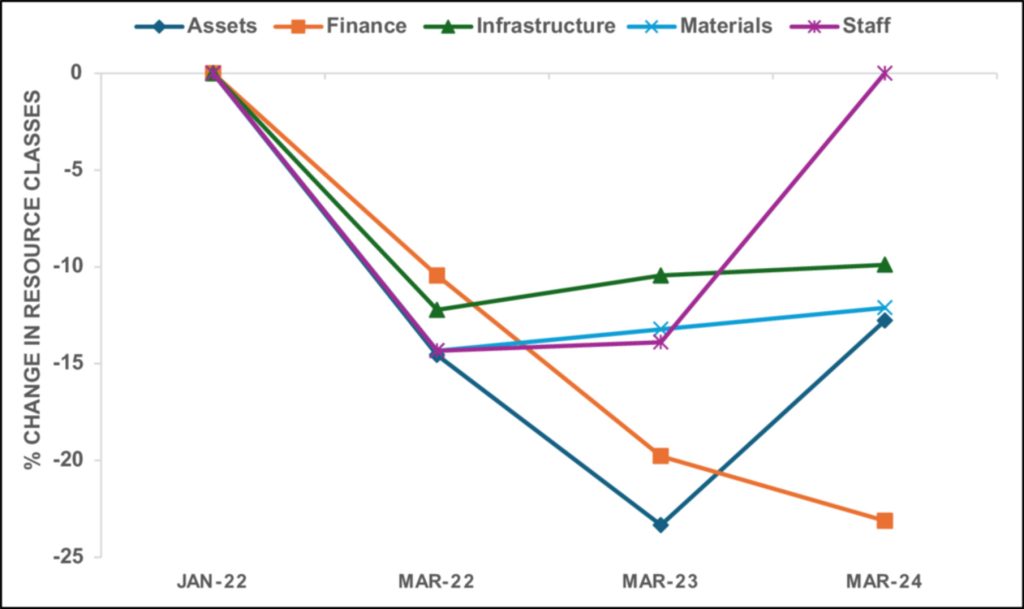

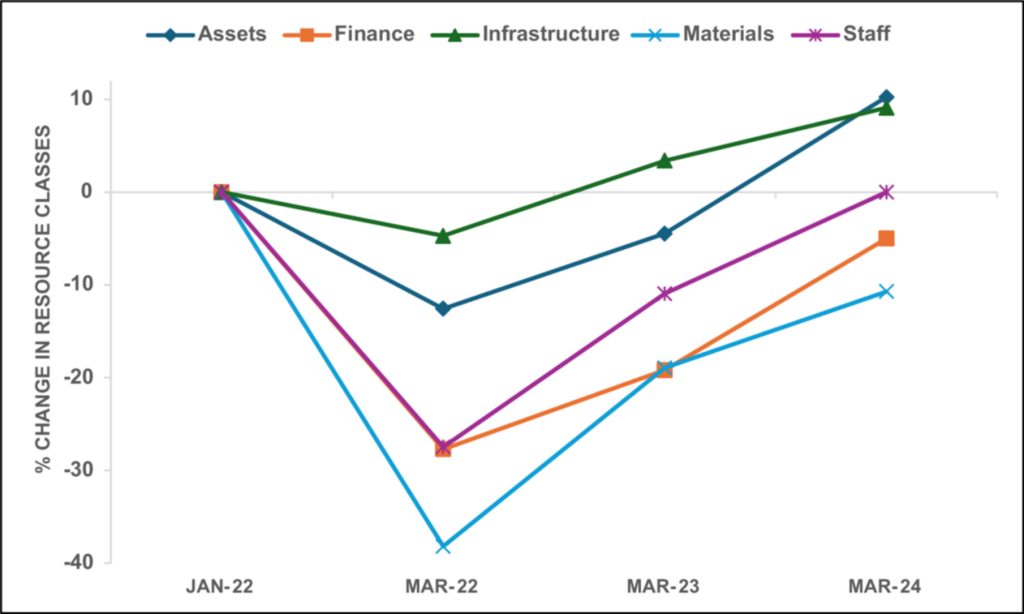

Another major factor influencing revenue changes was the war’s impact on firm resources. This factor includes five sub-categories: (a) the firm’s assets (serviceability of equipment, machinery, production or service delivery assets); (b) availability of firm infrastructure (physical buildings, water and electricity supply, communications networks, etc.); (c) access to capital for continued operations and growth; (d) access to raw materials and essential components for production and service delivery; (e) availability of staff to produce the firm’s output. The assumption is that the war likely negatively impacted each of these resources to varying degrees, and that resilient firms would eventually attempt restore these resources to near pre-war levels, or perhaps to even exceed them. We retrospectively measured these five resource classes over three periods and report the data falling within each of the respective organisational resilience pathways in Figures 7–10.

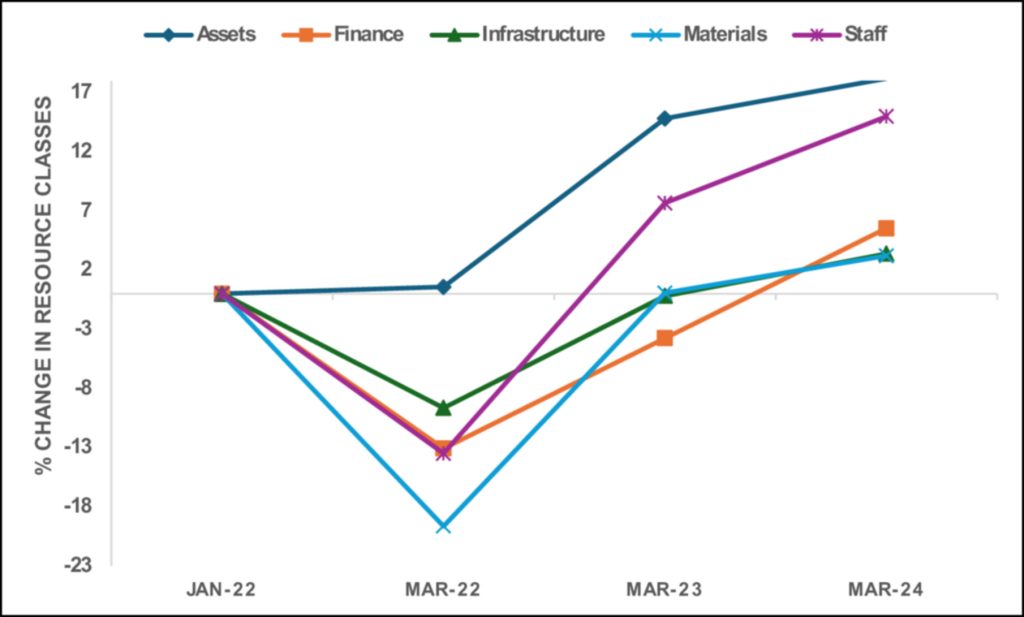

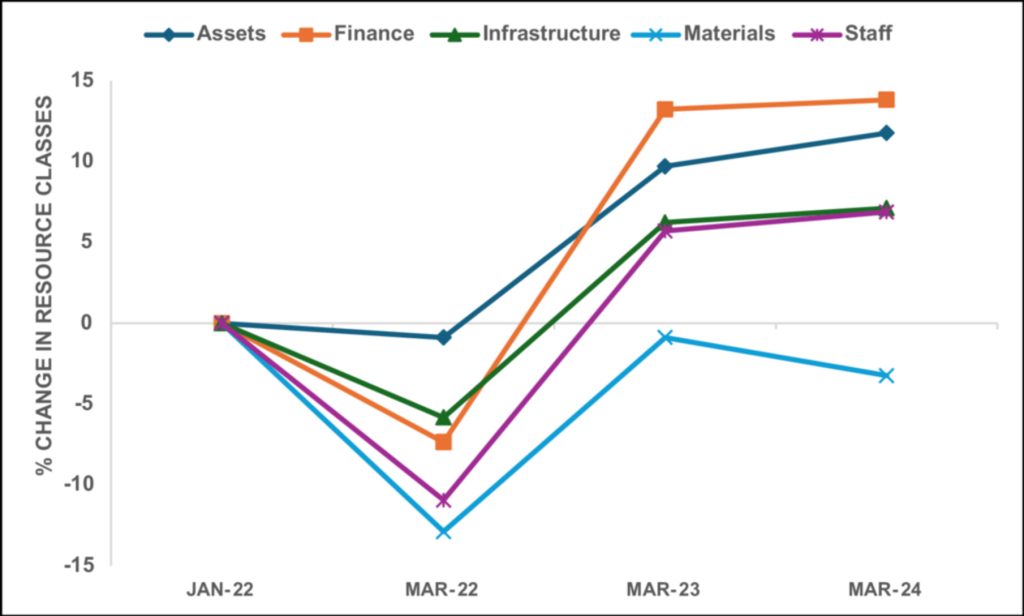

First, we examine the bounce-less category of firms (Figure 4). Two factors contributed to their gradual revenue loss and inability to recover over the review period: (1) an average market demand loss of −36% for products and services (reported above) and (2) a 10% to 25% reduction in all resource classes (see Figure 7) over the entire period except for the staff resource, which recovered to 0% change by March 2024. This double blow provides a strong indication as to why these firms have not yet bounced back.

Next, we consider the bounce-back category of firms, which experienced an average market demand change of −25%. This aligns with the revenue trend line, which dropped by 62% in March 2022 and then rebounded to −30% and −15% over the subsequent periods. The drop in demand likely influenced the revenue trajectory for these firms. This group also faced significant shocks to all resource classes immediately after the war’s outbreak (see Figure 8), but gradually recovered to varying degrees. The largest shock was in access to raw materials (−38%), followed by −27% in both access to staff and funding. Assets and infrastructure experienced relatively small shocks of less than 10%, and these were the only resource classes that ended up with positive 10% changes by the end of our measurement period. This pattern suggests strong inherent organisational resilience, enabling these firms to recover to pre-war revenue levels and rejuvenate their resources, even exceeding pre-war levels in some cases (i.e., infrastructure and assets). Access to raw materials remained a challenge, albeit gradually improving from −38% to −10%. Access to funds also improved after the initial shock, possibly due to government support and international aid. Within this bounce-back pathway, despite significant resource setbacks and a considerable decline in product/service demand, resilient behaviour enabled these firms to nearly return to pre-war levels.

The bounce-beyond category was the first to experience a positive demand change of 10.3%. However, organisations falling within this pathway faced significant resource shocks in all categories except assets in the early months, as shown in Figure 9. Their revenue initially dropped by 50%, but they managed to realign and reestablish themselves, eventually exceeding pre-war resources and improving revenue by nearly 50% relative to pre-war levels in the final measurement period. Except for assets, all other resource categories experienced shocks between −10% and −20% but recovered to higher levels than those they were achieving before the war. Notably, access to staff increased to +15% above pre-war levels by the end of our measurement period. This could be due to more women joining the workforce to compensate for men lost to conscription. Within this pathway, we see displays of resilience, as these firms overcame significant resource setbacks and benefited from increased demand for their products/services.

What distinguishes firms in the bounce-boom category from the other categories is that revenues immediately increased in the face of much stronger market demand for products and services ( ~35% increase). However, firms in this category did not escape resource shocks, although they were relatively small compared to the other categories, between 0% and 13% (see Figure 10). The largest shocks were in access to raw materials (−13%) and loss of staff (−11%). However, these setbacks were brief, and all resource categories, except raw materials, returned to above pre-war levels shortly thereafter. The persistent challenge with raw materials is consistent with the previous categories, as goods typically become scarce during war.

6 Discussion

In this article, we examine resilience through the lens of the impact of war as a crisis shock on firm revenue, market demand, and resources. Our findings reveal several significant contributions to both theory and practice in the field of organisational resilience. First, to our knowledge, we are the only research team to collect and explore real-time, longitudinal measurements of resilience paths using firm revenue within an active war (as seen in Figure 4). Prior authors have explored these paths conceptually, but none with empirical data representing such a widespread number of organisations, industries, and geographic locations across a 2-year timeframe following the shock of a full-scale war. This is a significant contribution as we were able to assess the fit of existing theoretical models through empirical analysis.

Second, our findings confirmed the presence of the two resource pathways described within the extant literature, bounce-back and bounce-beyond, and extend our understanding of one of them, the bounce-back pathway. Although the individual firms falling within this category have not recovered to what previous authors have referred to as a balanced state (Hoegl and Hartmann 2020) (i.e., their position before the shock or setback), the firms have made progress in terms of recovering from the initial resource decline immediately following the shock. Within Hoegl and Hartmann’s (2020) model, only firms that achieve equal to or greater than the position they were in before the shock are classified as ‘bouncing back.’ We view our data as indicating otherwise. We argue that it is more logical to define the bounce back resilience pathway as representing firms whose respective performance measure (in our case, firm revenue) recovers anywhere between the initial shock’s low point and the balanced state. We believe it is not practical or meaningful to only refer to companies that return to their balanced state as bouncing back. In other words, we believe bounce-back should not be seen as a single-value (reference point = 0) recovery event, but rather, as a continuum of events as our data suggest. We view bounce-back as an ongoing process, noting that resilience paths are fluid and that resilience manifests over time.

Third, we identify two new resilience pathways. The first we have labelled bounce-boom. Firms in this category have been hit by the same crisis shock as those in other categories (arguably to different degrees because of variables such as geographical distance from the war, industry type, changes in market demand, etc.), but they have not experienced a performance decline with regard to revenue. We credit firms in this category as being resilient because they experienced significant declines in their organisational resources such as employees, infrastructure, equipment, materials, and capital. This finding extends the scope of what can be considered as firms demonstrating resilience to when a firm is negatively impacted in one or more of its resource bases, yet they are able to improve performance in terms of revenue. Here, our findings challenge the theoretical framework proposed by Bartuseviciene et al. (2022). They suggest that a bounce-back stage is a prerequisite for a successful bounce-forward (or bounce-beyond) phase, yet our findings present a more nuanced perspective highlighting the variability of growth or decline based on which variables are examined as determinants of resilience. We have shown that firms in our bounce-boom category experienced no decline in revenue (hence, there is no bouncing back with respect to this variable), yet they did experience shocks and recoveries in their resource base. These firms were able to capitalise on favourable conditions and elevate their performance without undergoing a period of decline and subsequent recovery. However, it is important to note that the resource shocks observed by our bounce-boom firms could be interpreted as a form of bounce-back, albeit not in the traditional sense of requiring an immediate revenue decline. This observation adds complexity to our understanding of the organisational resilience process and suggests that the relationship between bounce-back and bounce-beyond pathways may be more intricate than previously conceptualised.

With respect to the second pathway we identified, bounce-less, we are also extending the literature by proposing that firm survival following a crisis shock is, in fact, a recognised pathway for resilience. We view resilience as continuing to operate your organisation, even if it is at a loss, following a shock. The organisations falling within this pathway may still have gradual revenue loss and not yet have figured out a way to recover from the crisis shock, yet they are still operational. They are providing jobs for their employees and products or services for their community. Their resilience, in many ways, is clearer than the others because they are still fighting to survive even with a significant loss in market demand and a reduction in all resource classes except for employees. In terms of their employees, they have returned to pre-crisis levels. With employees comes stability and the ability to continue to fight, as these bounce-less organisations are doing. They are fighting. As above, our contribution to the literature with the new ‘bounce-less’ pathway is the inclusion of survival as a criterion for resilience, regardless of the data regarding other more traditional markers (e.g., market demand, firm resources, revenue). To continue to fight and remain operational is to demonstrate resilience.

Taken together, our findings indicate that organisational resilience is a multifaceted process, potentially involving different pathways to recovery and growth. While firms in the same pathway (e.g., ‘bounce-back’) may share similar outcomes, their resilience profiles are shaped by unique temporal and contextual interactions. We concur with scholars who have cautioned that the recovery phase is a critical but often neglected aspect of resilience (e.g., [Darkow 2018]). Instead of merely ‘bouncing back’ to a previous state, organisations should aim to achieve a ‘new normal’ that may be more advantageous. While learning from setbacks can be valuable, as Bartuseviciene et al. (2022) suggest, our research shows that immediate capitalisation on opportunities can also lead to enhanced organisational performance. This nuanced understanding of resilience aligns with recent perspectives that view it as a dynamic capability, allowing organisations to adapt and thrive in various circumstances (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011; Maor et al. 2024). It underscores the importance of considering multiple factors, strategies, and resultant pathways when assessing and developing organisational resilience (Maor et al. 2024).

7 Limitations

This article has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size of 75 Ukrainian firms, while providing valuable insights, may not be representative of the broader population of businesses affected by war, limiting the generalisability of the findings. Secondly, the reliance on self-reported data from surveys could introduce biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias, affecting the accuracy of the results. Additionally, the study’s focus on a specific conflict, the war in Ukraine, may limit the applicability of the findings to other armed conflict scenarios with different geopolitical characteristics and impacts. Finally, the dynamic and ongoing nature of the war presents challenges in capturing the full extent of its long-term effects on organisational resilience, as the situation continues to evolve. Future research should consider larger, more diverse samples and longitudinal studies to address these limitations and further explore the interplay between resource shocks and performance metrics, as well as the long-term implications of different resilience trajectories.

8 Conclusion

This study provides significant insights into organisational resilience in the context of prolonged crisis, specifically the ongoing war in Ukraine. Through longitudinal data collected from organisational decision-makers in 75 unique Ukrainian firms, we have made several novel contributions to the field as outlined in our discussion section. These contributions collectively paint a more complex picture of organisational resilience, highlighting its multifaceted nature and the various pathways to recovery and growth. Our research underscores the importance of considering multiple factors and strategies when assessing and developing organisational resilience, aligning with recent perspectives that view resilience as a dynamic capability.

The nuanced relationships across selected variables and resultant pathways, highlight the complex interplay of factors contributing to resilience. This complexity underscores the value of a multidimensional approach to assessing organisational resilience as a dynamic and time-sensitive concept, evolving based on the specific moment and observed variables. For instance, at our last observation point of March 2024, 2 years into the war, firms classified as bounce-back were positioned below the zero-point reference line. However, the upward trend indicates that they could potentially transition into the bounce-beyond category in subsequent periods. A similar argument can be made for firms in the bounce-less category; although they had not yet demonstrated any signs of recovery by March 2024, this does not preclude the possibility of future recovery. The mere fact that these firms have endured for over 2 years within an environment that has impacted every aspect of day-to-day organisational functioning suggests a latent yet powerful resilience that could manifest as they explore avenues for recovery.

This insight underscores a crucial lesson for management: resilience can enable firms to navigate through phases of adversity, moving from bounce-less to bounce-back, and in exceptional circumstances, achieving a bounce-beyond status. The potential for such transformation hinges significantly on the leadership qualities within these firms, specifically, how effectively they manage their resources, adapt to changing environments, and leverage external support and opportunities. Ultimately, our analysis reveals that even when faced with severe challenges such as declines in revenue, diminished demand for products and services, and resource constraints, resilient behaviour can facilitate progress through these challenging phases. The ability to recover from setbacks and strive for performance levels that either match or exceed pre-crisis shock benchmarks is a testament to the potential of organisational resilience.

In conclusion, our research provides new knowledge about the various organisational resilience pathways exhibited by firms operating within an active and ongoing war. Our findings provide a foundation for more nuanced theoretical models of organisational resilience and offer practical guidance for firms navigating prolonged adverse events. Future research should further explore the interplay between resource shocks and performance metrics, deeper causal relationships between factors, as well as the long-term implications of different resilience trajectories.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the organisational leaders who contributed their time so generously while living within war to share their thoughts and organisational data with us for this study. Open access publishing facilitated by Bond University, as part of the Wiley – Bond University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.